Image description: Two floating heads with colorful makeup and hair are in conversation with each other. One has a thought bubble that's filled with the word "power" emerging from the top of their head, the other has a long speech bubble (shaped like a whale) that also has the word "power" repeated. The background is colorful and abstract with diagonally intersecting lines and decorated with stars and eyes.

We’re following up on our previous blog around Grappling with Feedback. If you missed the first part, read Grappling with Feedback: Lessons in Trying, Failing, and Trying Again here.

words and illustrations by Learkana Chong

In my previous blog about giving and receiving feedback, I explored some of the lessons I’ve learned, and am still learning, on my personal journey of embracing feedback as a transformative practice. But all of the lessons I’ve shared are null and void if power isn’t taken into account. Power, as we understand it at CompassPoint, is the capacity to influence outcomes that affect you and others. In this blog, I'm exploring the challenges of giving feedback across two dimensions of power—racial power and positional power.

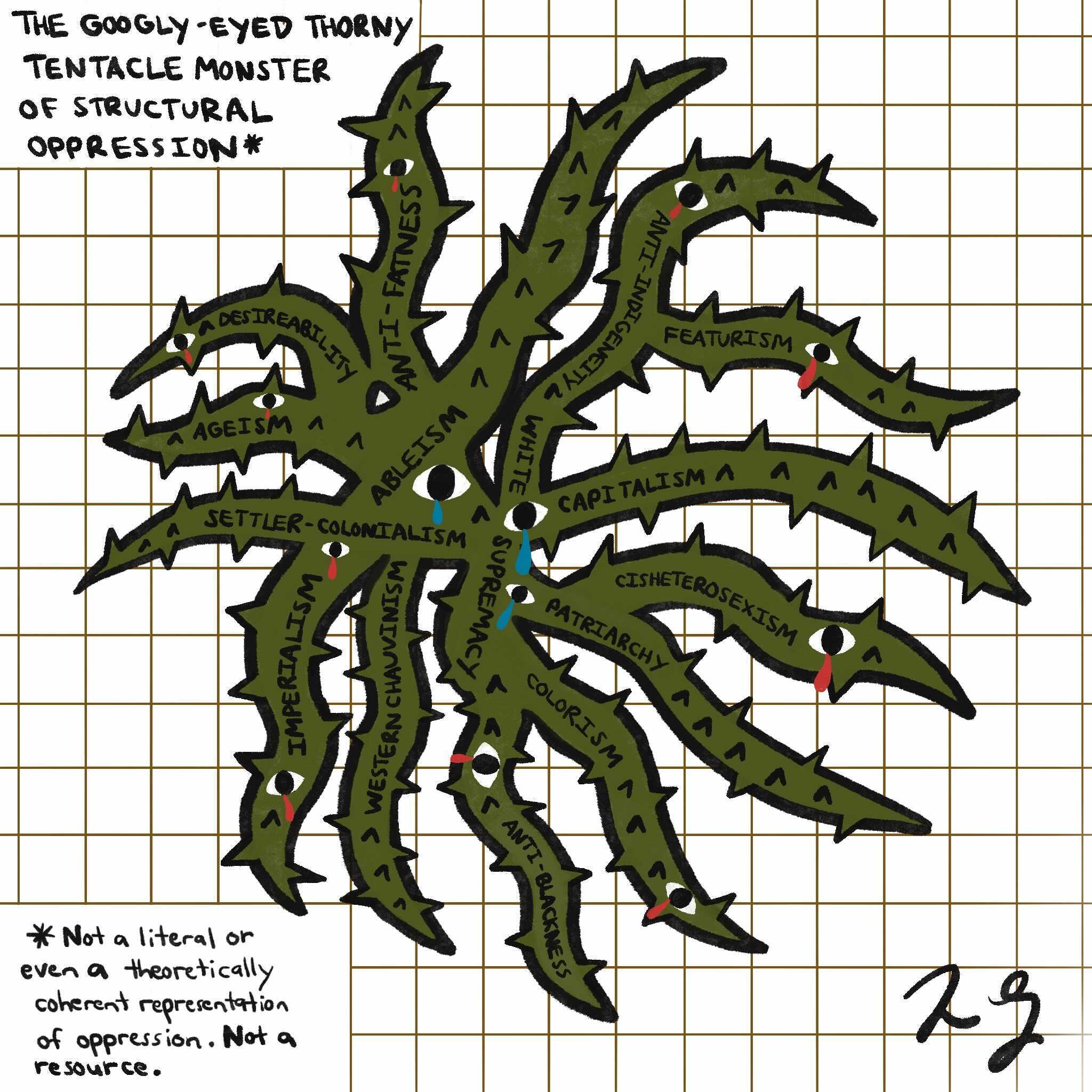

It’s important to practice self-awareness around power dynamics when it comes to feedback, which includes both positional power within an organizational structure and social power derived from structural forms of oppression一capitalism, white supremacy, patriarchy, ableism, and more. Grappling with feedback without considering power dynamics can replicate the systems of oppression we should be dismantling. This is particularly crucial for those of us who work at social justice and nonprofit organizations. Our missions and external bodies of work may be liberatory and anti-oppressive, but can we also say the same about how we are in relationship with one another? Our vision for social justice should not be limited to our mission statement and our programs; it should apply to our workplace culture and norms, too.

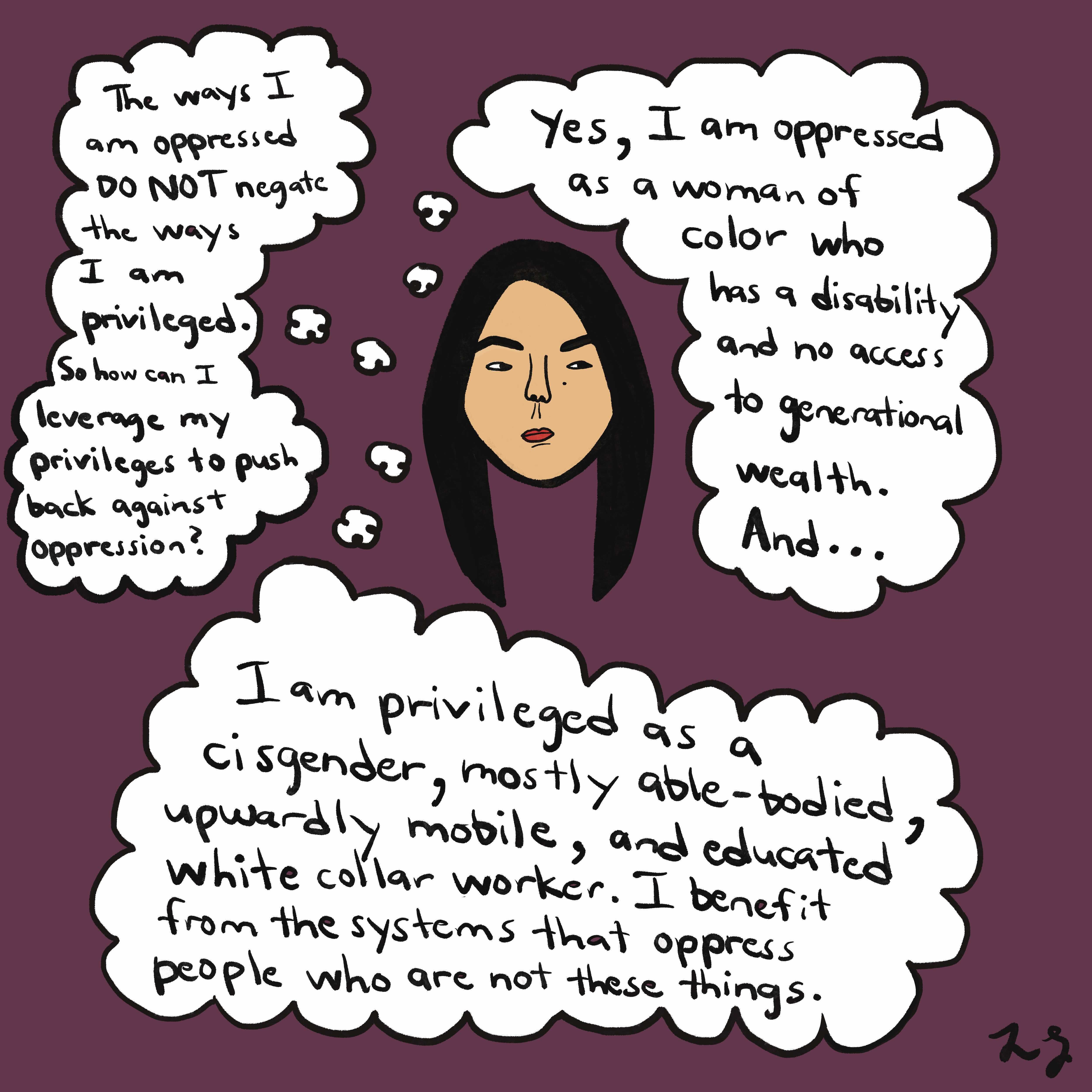

We are all positioned within intersecting systems of oppression, and most (if not all) of us are situated along at least one axis of privilege and power. Although I cannot dismantle the systems of oppression that I benefit from on my own, I can certainly recognize and leverage the power and privilege I do have in ways that offset harm一which includes doing so in the context of my day-to-day interactions with people I work with and am in community with.

I say all of this with the caveat that I am by no means an expert when it comes to navigating power. There have been plenty of times when I failed to exercise my own power thoughtfully, resulting in hurt or harm experienced by others. A commitment to addressing power and unlearning oppression doesn’t mean I never mess up; it just means I am steadfast in learning from my mistakes and trying to do better.

Image description: A floating head with long black hair, beige skin, and red lips has a contemplative look on her face as three big, white cloud-shaped thought bubbles surround her. The text in the thought bubbles can be read as follows:

- Top right bubble: Yes, I am oppressed as a woman of color who has a disability and no access to generational wealth. And…

- Bottom bubble: I am privileged as a cisgender, mostly able-bodied, upwardly mobile, and educated white collar worker. I benefit from the systems that oppress people who are not these things.

- Top left bubble: The ways I am oppressed DO NOT negate the ways I am privileged. So how can I leverage my privileges to push back against oppression?

Considering Social Power in the Context of Feedback

At CompassPoint, we have been having critical conversations about anti-Blackness and what it looks like to build Pro-Blackness at our multiracial organization. I have witnessed and participated in these conversations within an organization-wide setting, within my racial affinity group, and within myself.

As someone who is conferred social power by structural anti-Blackness because of my lived experience as a non-Black person, I must work to actively interrupt the socially conditioned anti-Blackness within myself. For me, this means that I am always trying my best to be attentive to my rationale and emotional responses when I am receiving feedback from a Black colleague and when I am preparing to give feedback to a Black colleague.

Is my thinking and feeling in relation to this person reinforcing existing narratives and stereotypes rooted in anti-Blackness, even if it is unconsciously? Here are a few questions I might ask myself to unpack this further:

- Would I react, respond, or show up to the conversation differently if the colleague in question wasn’t Black?

- Have I reacted, responded, or shown up to a similar conversation differently when the colleague in question wasn’t Black?

- What things could I say or do that get to the heart of the matter without potentially causing a harmful impact?

- What things should I not say or do that might cause a harmful impact?

My colleague Jasmine Hall also stresses the importance of non-Black folks first and foremost reflecting internally as a way to move towards being pro-Black in the feedback process. “The stereotype about Black folks being aggressive, and the stereotype of ‘The Angry Black Woman,’ makes it challenging for [non-Black] folks to give [Black people] feedback. The biggest thing that helped me for non-Black folks that are giving me feedback is around challenging assumptions that you might have about me, or really unpacking those things before you engage in the conversation.” This doesn’t mean you should never give a Black person critical or developmental feedback, however; as Jasmine points out, a lack of willingness to engage in hard conversations with Black people can also be anti-Black. “I don't need a ‘sandwich,’ I don't need [critical feedback] softened up. I don't need it to look pretty or to smell good or to even be said in a ‘clean’ way or a perfect way. But I do expect respect.”

While I name anti-Blackness here specifically, this approach and these kinds of reflection questions can also inform how one might want to personally unpack and disrupt misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, anti-fatness, and other forms of oppression. For me, it’s crucial to continuously reflect on these sorts of questions in earnest, and to consider that my words and actions may be contributing to interpersonal and structural harm一regardless of my intentions of being “good.” “Accountability is crucial here,” says my colleague spring opara. “And apologizing for ‘impact’ doesn’t necessarily take away from my intent.” She offers a maxim shared with her by Jasmine to emphasize her point: “Multiple truths can exist at the same time.”

Being able to identify my social power and privileges is only a first step. Actually putting into practice that self-awareness一by checking my assumptions, prioritizing listening, and holding myself accountable in conversations where I am being called in or called out by someone who doesn’t have the same social power and privilege as I do, for instance一is what can make a tangible difference. Yes, I will make mistakes and I have made mistakes, again and again. But what I’ve learned is that real solidarity is a never-ending journey: I will never arrive at a place of perfect allyship, but I am determined to keep going because of a deep and unconditional love for the healing and liberation of all people, and the unshakeable belief that I must play a part in it.

Image description: A googly-eyed, thorny, green tentacle monster personifying intersecting forms of structural oppression, set against a background that looks like graph paper. The following words are inscribed on its tentacles: anti-Indigeneity, white supremacy, anti-Blackness, colorism, patriarchy, cisheterosexism, capitalism, featurism, Western chauvinism, imperialism, settler-colonialism, ableism, ageism, desirability, anti-fatness. In the top left corner is a white square that reads “THE GOOGLY-EYED THORNY TENTACLE MONSTER OF STRUCTURAL OPPRESSION*.” In the bottom left corner is another white square that reads “*Not a literal or even a theoretically coherent representation of oppression. Not a resource.”

Interrupting Positional Power in the Context of Feedback

I don’t possess much experience with having positional power over other people within a hierarchical organizational structure. (By “positional power,” I mean occupying a formal role at an organization in which one is able to make decisions that dictate or shape the work of another person or multiple people.) What I can speak to, however, is the experience of engaging in the feedback process as someone with less positional power.

Fear of being reprimanded, written up, perceived as insubordinate and not considered for promotion, or worst of all, fired, has taught me to be hesitant when it comes to speaking my truth or being my authentic self with people who have positional power over me. Sometimes this has resulted in me trying to be as accommodating as possible and remaining silent, even if I experience a negative impact caused by a person with positional power over me or disagree with a decision made that directly affects me.

Social power and positional power often work in tandem within organizations. For example, it is no surprise that white people, who hold the most racial power, are more likely to hold greater positional power in an organization, due to how systems of oppression shape our institutions. But even when that isn’t the case, being on the receiving end of someone inconsiderately flexing their positional power alone can lead to harmful and punitive consequences for people with lesser positional power.

With that said, I want to share some insights on what someone with greater positional power can do to exercise mindfulness of their power in a way that positively impacts people with less positional power.

Someone with positional power can:

- Take care to share the specific context and “why” behind their feedback to someone who has less positional power, and explicitly disclose the implications or consequences of that feedback.

- Make more time and effort to provide detailed affirmative feedback to someone with less positional power, rather than only or disproportionately offering critical feedback.

- Work on listening from a place of wanting to understand, affirm, learn from, and offer thought partnership to a person with less positional power, rather than listening to “fix” what they perceive to be the “real” problem and responding with paternalistic advice.

- Explicitly and consistently invite people with less positional power to give them critical feedback without fear of retaliation, and model how to receive such feedback with humility, thoughtfulness, and grace.

- Create opportunities for people with less positional power to share input on and exercise a level of control over their (individual and collaborative) work prior to any final decisions made about their work, resulting in people with less positional power feeling seen, heard, affirmed, empowered, and valued.

- Muster the courage to step into vulnerability with someone who has less positional power, in order to shift away from a transactional relationship that is superficial and mutually unfulfilling, and towards a transformative relationship built on witnessing and embracing each other’s wholeness.

In the workplace, those with the greatest decision-making power must foster the conditions for a healthy culture of feedback to blossom, and that must include creating a safe environment for all staff to offer feedback, including and especially staff with less positional power and staff who experience the brunt of structural oppression.

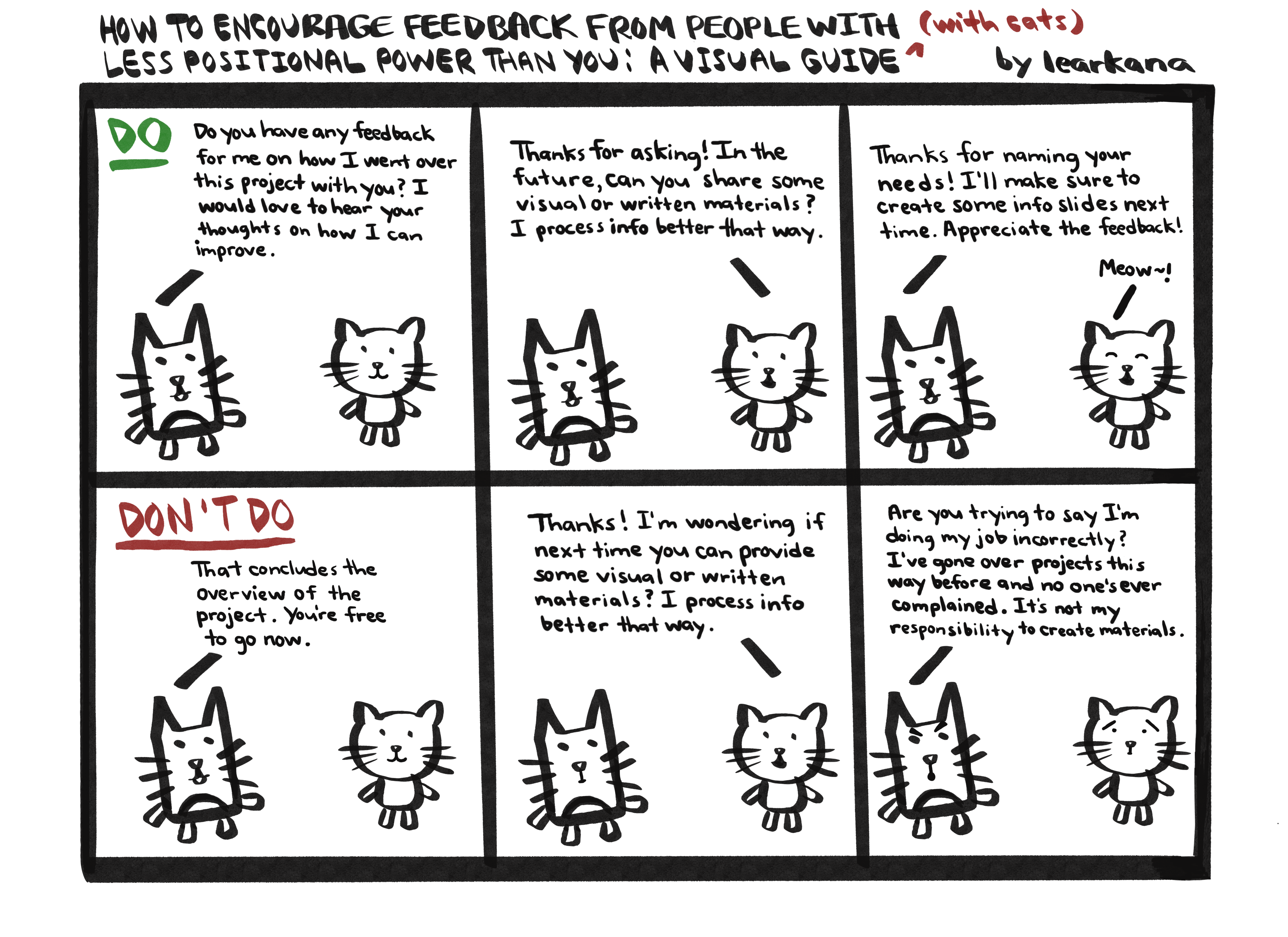

[Click the image below to expand it!]

Image description: A black and white 6-panel comic on “How to encourage feedback from people with less positional power than you: a visual guide with cats,” starring 2 doodle-style talking cats.

The first three panels illustrate what people should DO, using the following dialogue:

Cat 1: “Do you have any feedback for me on how I went over this project with you? would love to hear your thoughts on how I can improve.”

Cat 2: “Thanks for asking! In the future, can you share some visual or written materials? I process info better that way.”

Cat 1: “Thanks for naming your needs! I’ll make sure to create some info slides next time. Appreciate the feedback!”

Cat 2: “Meow~!”

The final three panels illustrate what people should NOT do, using the following dialogue:

Cat 1: “That concludes the overview of the project. You’re free to go now.

Cat 2: “Thanks! I’m wondering if next time you can prove some visual or written materials? I process info better that way.”

Cat 3 (now has angry eyebrows): “Are you saying I’m not doing my job correctly? I’ve gone over projects this way before and no one’s ever complained. It’s not my responsibility to create materials.”

The examples I’ve provided around anti-Blackness and positional power within a hierarchical organizational structure are not the only kinds of power dynamics that may show up in an organization; I’ve shared those reflections here in hopes that there is some resonance that can be found in my own perspective on my personal experiences.

I also want to name that power dynamics are often not a simple binary in real life (e.g., Person A has all the power and Person B has none of the power), nor are power dynamics inherently, necessarily, or inevitably harmful and exploitative. What I am inviting folks to consider alongside me is how our relationships to social or positional power inform or influence how we give and receive feedback to others, and conversely, how others give and receive feedback to us. In what ways can we tap into our power within so that we are conscientious about using our individual access to social or positional power in service of others who are oppressed or disempowered in ways that we are not?

Being mindful of power dynamics means people are holding themselves accountable for how they impact those who don’t share the same power and privilege as they do in a particular context. While the onus is on everyone to be conscious of what power in the room looks like, the greater responsibility falls on the people who wield the most power (social and positional) relative to others in a given situation. And being truly mindful involves a practice of self-awareness: I say “practice” because I believe self-awareness isn’t a passive trait that a person simply has; it’s a skill that needs to be actively worked on and requires ongoing development一and it is necessary if we are serious in our commitment to equity and justice in the relationships we build with people.

Resources that have informed or inspired this blog post:

Supervision: Relationships & Structures That Help Us Thrive (CompassPoint training)

Supervision for BIPOC Leaders (CompassPoint training)

Coaching Skills for Leaders (CompassPoint training)

Conflict Resolution with Power and Privilege in Mind (CompassPoint training)

“Maintaining Difference,” a written series from Conflict Transformation | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

Conflict Skills Course from Luna N. Hughson

Turning Towards Each Other: A Conflict Workbook by Jovida Ross and Weyam Ghadbian

Special thanks to Jasmine Hall and spring opara for their critical input on and support of this blog post; shoutout to Steve Lew and Rebecca Aced-Molina for their encouragement, support, valuable insights, and modeling of feedback. Also, deep appreciation to my fellow CompassPoint Asian affinity members, past and present, for our shared commitment to exploring feedback and unlearning anti-Blackness in community with each other.

Submit a comment