Image description: Two disembodied heads look at each other against a blue background. The one on the left has long blonde curly hair, a dark brown complexion, bright brown eyes accentuated by pale green eyeshadow, a dangly pale green earring hanging from each ear (each earring is shaped into the word “vulnerability,” written in cursive), oval-shaped spots of baby pink blush on their cheeks, and rosy lips. A white speech bubble illustrated to look like a fish comes out from their mouth. Black text within the fish bubble reads “feedback,” repeated x10 in cursive. There are little black and white music notes by the fish bubble’s mouth. The head on the right has a lighter brown complexion, darker brown eyes accentuated by lashes and lavender eyeshadow, short curly black hair and a curly black beard, double gold hoop earrings in each ear, oval-shaped spots of salmon pink blush on their cheeks, and pale pink lips. There are little black and white hearts, spirals, raindrops, and squiggles decorating the backdrop as well.

Giving and receiving real feedback can be deeply transformational in our nonprofit organizations and in social justice spaces. But that doesn't mean it's easy! Sharing our truths means embracing complexity and making space for messiness. We're exploring what authentic feedback demands of us and why it's worth it.

words and illustrations by Learkana Chong

Feedback has been on my mind and in my heart often these days. For me, it has become a tangible path towards transformative relationships rooted in trust and care, towards accountability in our social justice spaces and movements, and towards an interdependent, community-oriented world in which we are able to focus more on healing and thriving.

I haven’t always felt this way about feedback. It was only when I began working at CompassPoint two years ago that I started experiencing and envisioning how feedback can and should be, beyond performance reviews and evaluation surveys, and extractive metrics. I think feedback, distilled into its purest form, is truth, and more specifically, the multiplicity of truth:

- the truth of how someone experienced me

- the truth of how I experienced them

- the truth of how we experience ourselves

- the truth of each of our thoughts, feelings, needs, hopes, fears, and values

- the truth of our relationships to power;

and, consequently, the tensions, the contradictions, the converging and diverging fractures embedded within this multiplicity of truth.

In our work to dismantle structural oppression and create a more liberated, just world, there needs to be more truth that is spoken of, listened to, and grappled with. Without truth, understood and held in all of its complexities, there can be no way for us to trust or grow with each other, let alone build a new world free from oppressive systems that have been built on and maintained by lies.

Grappling with feedback as a practice and a process is hard, messy work that requires humility, vulnerability, and honesty. And I believe it is the kind of work that is worth every ounce of effort we put into it. With that said, I humbly offer these lessons from my own personal journey with feedback, all of which I am still aspiring towards and learning.

Feedback is not just critical or negative

My associations with feedback have been mostly negative, and I am still in the process of unlearning that. Part of my misunderstanding stemmed from experiences of growing up and being around people who chose to share mostly negative feedback to me and little to no positive feedback. Because of this, I was conditioned to mistrust any positive feedback I received later in life and to expect only negative feedback, which I would then use to inwardly berate myself to do better. At a certain point (that is, talking to a coach with a therapist background), I realized this was simply reinforcing a toxic dynamic with myself that left me feeling deficient and unable to see my growth or even my capability for growth. I am now embracing a fuller, more holistic understanding of feedback, which is that there is affirmative or appreciative feedback (typically seen as more "positive''), and there is also critical, constructive, or developmental feedback (typically seen as more “negative”), and both are equally important to give and receive. For me, this means it’s important to specify the kind of feedback I am giving and receiving. “Feedback” in and of itself should not be used as a default for critical feedback.

Feedback is a gift

This applies to both affirmative and critical feedback. While this is certainly easier said than done (especially when it comes to critical feedback), actively working to shift my mindset about feedback has positively shifted my relationship to it. As uncomfortable as it can be to give or receive feedback, at the heart of this process is the belief in another person’s potential to listen, self-reflect, and grow, and the acknowledgment that we all have the power to impact other people. When I give feedback to someone else, I am recognizing that my thoughts and feelings are valid and worthy of being named and uplifted, and I am trusting that the other person will or has the capacity to recognize that as well. When I am receiving feedback, I try to be grateful that this person mustered up the courage and vulnerability to share their thoughts and feelings with me, even if my initial reaction might be to disagree and get defensive (in the case of critical feedback), or even minimize or deflect (in the case of affirmative feedback).

The feedback I give should be clear, direct, specific, and actionable

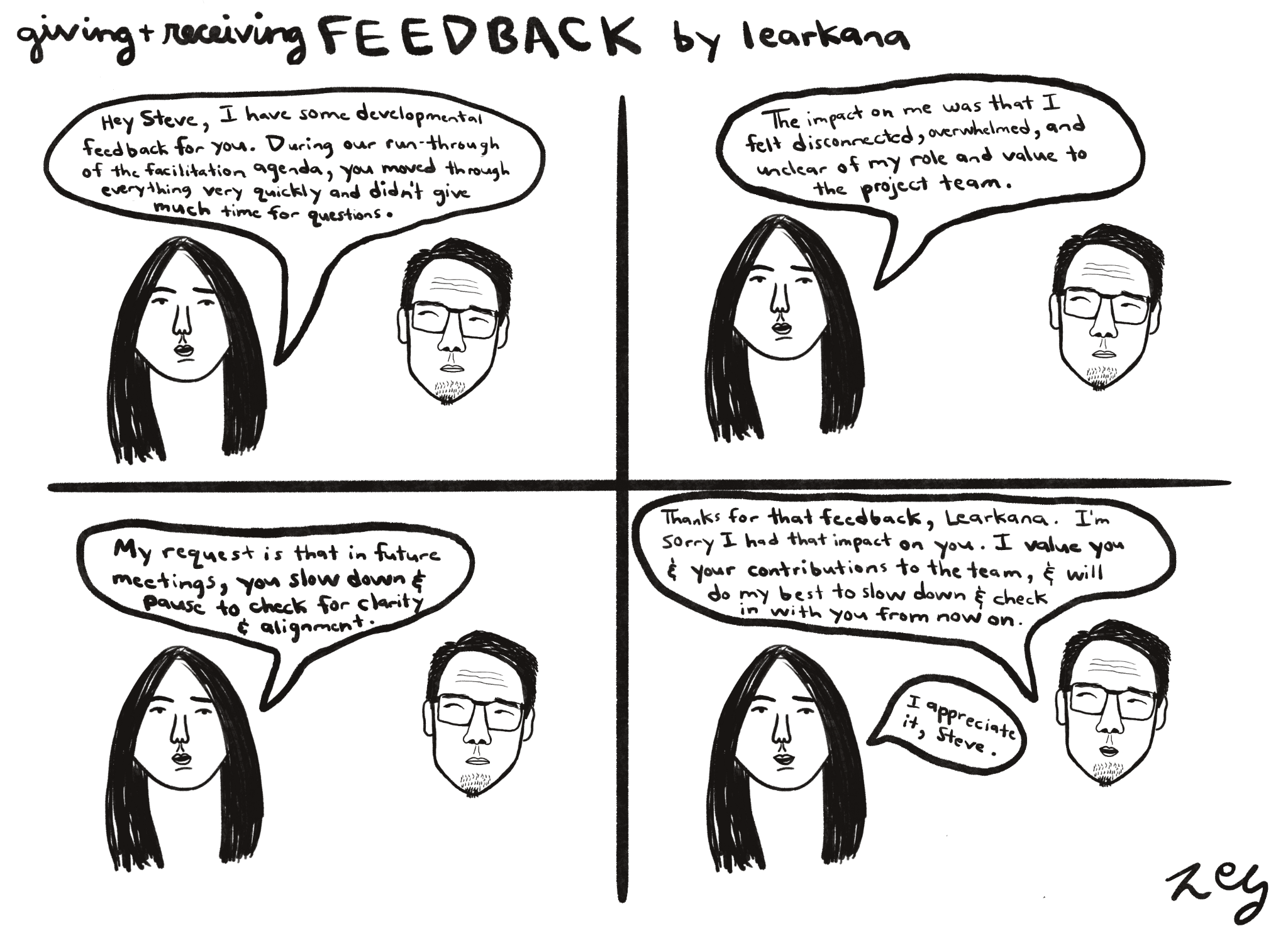

I’ve been learning that a big part of giving feedback is being able to communicate in a way that ensures the recipient of my feedback fully understands what I’m telling them and why, and to the extent possible, minimizes any confusion or tension that may be experienced by the recipient. This means I should communicate my feedback very plainly, without any unnecessary filler or niceties (particularly in the case of critical feedback). I should also take care to employ language that isn’t incendiary, judgmental, or patronizing--the goal for me is to honor someone’s ability to grow, and not to emotionally dump on someone. While there is no exact science to this, I have found it helpful to rely on a sort of skeleton for structuring the feedback I provide to someone, which is taught in some of our workshops at CompassPoint (including our Supervision: Relationships and Structures that Help us Thrive training) and is similar to what is taught in nonviolent communication:

Image description: A diagram that reads from the top center to bottom left in triangular fashion, “1) State the behavior → 2) Name the impact → 3) Make a request.” Between each phrase are two brightly colored flowers with yellow centers that share the same green stem and leaves, connecting the diagram through a floral arrangement. The numbers for the phrases (1), (2), and (3) appear in the centers of the flowers that are adjacent to each phrase.

Receiving feedback can be uncomfortable, and that’s okay

I’m just going to name upfront that no matter how thoughtful and considerate someone is when giving me feedback, the experience will never feel perfectly good or comfortable for me, especially in the case of critical feedback. I can very confidently say that I will never come away from receiving critical feedback thinking, “Wow! I unequivocally loved hearing this and would love to hear it on repeat!” This means I have had to learn and am continually learning to be okay with the discomfort that may surface for me, and it is my responsibility to parse out and unpack the source of this discomfort on my own time--not the person giving me the feedback. A goal of mine in every difficult conversation I have with another person is to embrace the “negative” emotions I may be feeling in the moment, without holding someone else hostage to those feelings. Of course, if the person giving me feedback is being outright disrespectful, condescending, or oppressive in their delivery, that is an entirely different story. But in most cases, I find that the discomfort I sit with is often simply a knee-jerk means of protecting myself--specifically, my ego and the story I hold about myself as a person, which should not go unchecked and unchallenged. Understanding and accepting that this discomfort is human and will happen again has been freeing and has built up my own receptivity to feedback, which, in turn, has paved the way for people to feel more comfortable with giving direct feedback to me.

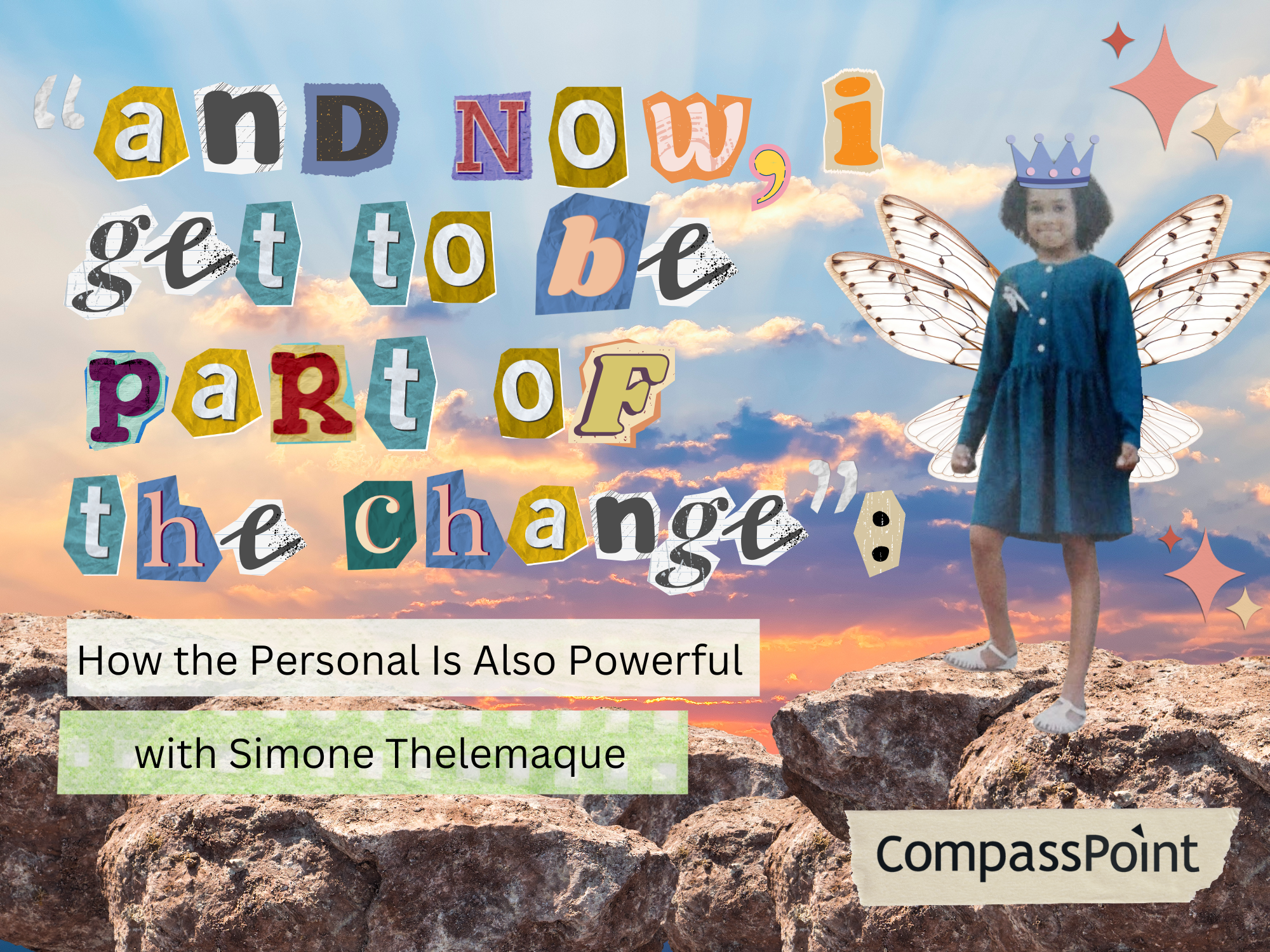

[Click the image below to expand it]

Image description: A black and white comic strip divided into four panels features two talking heads: the one on the left, named Learkana, has long dark hair parted in the middle, and the one on the right, named Steve, has shorter dark hair parted to the right, as well as square glasses, a few forehead wrinkles, a little scruff on the chin, and a goatee. At the top of the comic strip is the title and author name, stylized as follows: “giving + receiving FEEDBACK by learkana.”

The following dialogue appears in speech bubbles above each respective talking head.

Learkana (Panel 1): “Hey Steve, I have some developmental feedback for you. During our run-through of the facilitation agenda, you moved through everything very quickly and didn’t give much time for questions.”

Learkana (Panel 2): “The impact on me was that I felt disconnected, overwhelmed, and unclear of my role and value to the project team.”

Learkana (Panel 3): “My request is that in future meetings, you slow down and pause to check for clarity and alignment.”

Steve (Panel 4): “Thanks for that feedback, Learkana. I’m sorry I had that impact on you. I value you and your contributions to the team, and will do my best to slow down and check in with you from now on.”

Learkana (Panel 4): “I appreciate it, Steve.”

I share these offerings as food for thought and resonance, and not as a prescriptive, exhaustive step-by-step list that will guarantee the reader certification in “Feedback Skills 101” upon completion. I honestly don’t think there is a decisive way of being or becoming good at feedback; in fact, I would argue that it’s not so much about being “good” at feedback as it is about trying. And by “trying,” I mean doing the following things a very large number of times: listening, messing up, learning how to apologize, admitting when you’re wrong (to yourself and to other people), paying attention to growth (within yourself and others), sharing your feelings, saying things you mean and saying these things as precisely as you can, expressing gratitude to people out loud, naming your needs, and letting go of what no longer serves you.

Feedback, when done in earnest and with empathy, can be an antidote to white supremacy culture, and intersecting forms of oppression. It’s about being honest, authentic, and vulnerable with each other and ourselves. It’s about honoring and celebrating our individual and shared humanity, even when it feels hard and messy and ugly. It’s about pushing through the fragility of our egos and our privileges so we can see and actualize a fuller picture of ourselves in relation to the rest of the world. It’s about co-creating relationships that are whole, heartfelt, and nourishing for everyone involved. It’s about recognizing that the truth of the matter is, we need each other, and that has never not been true.

Resources that have informed or inspired this blog post:

Coaching Skills for Leaders (CompassPoint training)

Conflict Resolution with Power and Privilege in Mind (CompassPoint training)

“Maintaining Difference,” a written series from Conflict Transformation | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

Turning Towards Each Other: A Conflict Workbook by Jovida Ross and Weyam Ghadbian

Special thanks to Steve Lew and Rebecca Aced-Molina, for their encouragement, support, valuable insights, and modeling of feedback.

Submit a comment